|

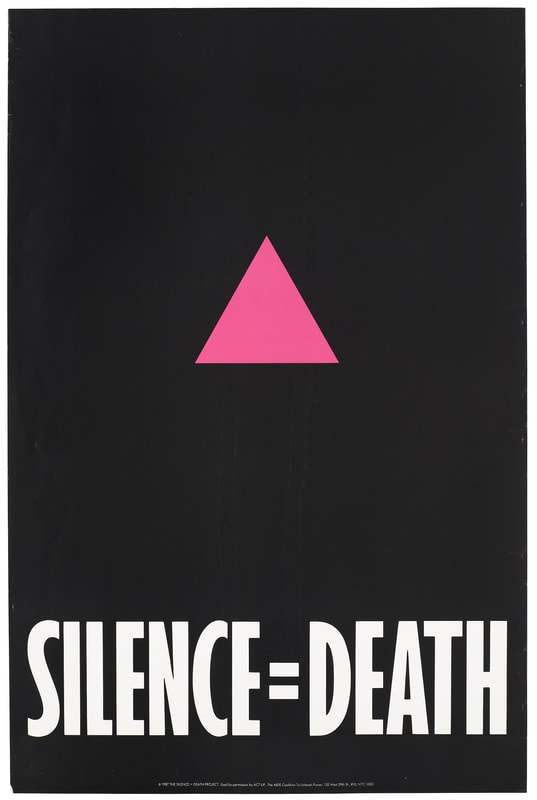

As the war in Ukraine wages on, luxury fashion brands have begun to a announce donations, events and fundraisers to support its victims – but this is far from the first crisis situation the fashion industry has had to contend with... It may seem strange to look to the fashion industry for a response in times of war and crisis. What, after all, do clothes have to do with geopolitics or pandemics? But, while in practical terms the actions of governments and international political bodies are clearly more important, there are several reasons fashion should be expected to do its part in times of crisis. Firstly, the fashion industry is worth $1.6 trillion dollars globally – roughly the same size as that of Russia. And, while estimates vary, it’s also suggested that fashion employs an estimated workforce of up to 430 million people, or one in every eight of the world’s workers, with almost every country across the globe represented in that workforce. Fashion, it’s clear, is a seriously powerful business with tentacles that reach far and wide, and influence that extends far beyond our wardrobes. Then there is also the fact that fashion as an art form has long acted as a reflection of the world around us. From feminism and immigration to abortion rights and homelessness, designers have long found inspiration in society’s thorniest issues and a voice with which to address them in their collections. It would, frankly, be remiss of designers not to act in times of global crisis – especially given the large social media followings brands and designers often have, which can act to amplify the message. All this has, of course, been brought into a renewed spotlight by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which broke out during the SS22 fashion show season. While the industry initially faced criticism for being slow to respond, while continuing with the show schedule as normal, as the death toll climbed and millions of Ukrainian civilians were displaced from their homes, brands finally began to announce charitable donations, fundraising initiatives and pauses on trade with Russia. More details on the luxury fashion industry’s response to the war in Ukraine can be found below. This is, however, not the first crisis that the industry has had to respond to. Read on for a brief history of the fashion industry’s response to everything from world wars to global pandemics. Fashion during World War OneThe fashion industry of the early Twentieth Century was very different to that which we know now, with much more production concentrated in factories in the UK, Europe and America. Many fashion houses, including Hermes in France and Burberry and Aquascutum in the UK, pressed their factories and workforces into creating military uniforms. Elsewhere, the industry put on fashion shows to help raise funds for the war effort, such as US Vogue’s editor-in-chief Edna Chase’s Fashion Fete in 1914. With Parisian designers forced to close their ateliers, the show highlighted designs by New York’s fashion finest and was attended by the city’s society elite both in attempt to raise money for the war effort and bolster the domestic fashion industry. Across the Atlantic, meanwhile, World War One actually gave rise to a whole new generation of design talent. Inspired to keep up morale through the joy of fashion, and with changing ideas about appropriate clothing giving them new licence to experiment and push boundaries, labels including Chanel, Vionnet and Charles Worth all found prominence during World War One. Fashion during World War TwoTo combat shortages and steeply rising costs, fabric rationing was introduced in Britain, Europe and the US during World Ward Two, spelling an extremely difficult time for many fashion houses. Faced with going out of business, many designers found innovative ways to work within the new system. In the UK, for example, designers including Peter Russell, Norman Hartnell, Bianca Mosca, Digby Morton, Victor Stiebel, Elspeth Champcommunal, Hardy Amies, Edward Molyneux and Charles Creed formed the Incorporated Society of London Fashion Designers. IncSoc was enlisted by the Board of Trade to create designs for a variety of economical outfits that could be manufactured using fabrics allowed by Britain’s Utility Scheme and in adherence with austerity rules. In Europe, fashion brands once again turned their hands to creating military uniforms. Coco Chanel manufactured pullovers for soldiers from her home in southern France while Elsa Schiaparelli is credited with the invention of the ‘siren suit’, a women’s jumpsuit complete with gas mask, hood and flask designed to help women stay presentable should they have to respond to an air raid in the middle of the night. Elsewhere, Mainbocher produced uniforms with the US Navy’s WAVES (Women Accepted for Voluntary Emergency Service) – the beginnings of a relationship with the US military that would last for decades. Inevitably, however, some brands found themselves on the wrong side of history, with Hugo Boss issuing an apology in 2011 for the part its eponymous founder played in designing uniforms for the Hitler Youth and its use of forced labour from Nazi prisoners. Fashion and the AIDS epidemic

Images from the event were seen around the world, emboldening others to begin taking action. In 1989 Susanne Bartsch organised the first Love Ball, inspired by Harlem’s drag balls, enlisting fashion brands like Donna Karan, Calvin Klein and Armani to form ‘houses’ to compete in voguing contests on the night. Tables were sold for $10,000 each and a second ball followed in 1991, with the two events raising over $3 million for DIFFA. The concept was then transplanted to Paris where Jean Paul Gaultier, Thierry Mugler, Cindy Crawford and Azzedine Alaïa walked in the Balade de L’Amour, while a third edition was held in 2019 featuring Billy Porter, Dapper Dan and Marc Jacobs. 1989 also saw Carolyne Roehm become president of the CFDA, a change in leadership that finally saw the industry body recognise its role in fighting the epidemic. The following year DIFFA and the CFDA teamed up, with help from Donna Karan, Ralph Lauren and US Vogue, to host the first Seventh on Sale event. The four-day retail event, attended by the public and stars including David Bowie and Iman, Naomi Campbell and Christy Turlington, raised more than $4 million for the New York City AIDS Fund, with designers such as Michael Kors, Bill Blass, Oscar de la Renta, Calvin Klein and Diane von Furstenberg donating merchandise. Following its success, a San Francisco edition and a second sale in New York followed, both raising millions of dollars and inspiring dozens of smaller fundraisers across the industry. How fashion responded to 9/11 and the war in AfghanistanJust as with the war in Ukraine, which began halfway through the SS22 fashion month, the 9/11 attacks took place during New York Fashion Week, meaning the industry was impacted both deeply and immediately. In the ensuing chaos, some of the remaining fashion week shows were cancelled with Fern Mallis, creator of NYFW, pivoting the event’s resources, such as bottled water and tennis, to aid the operation at Ground Zero. Elsewhere shows venues such as Lexington Avenue Armoury, where Donna Karan was scheduled to present her new collection, was repurposed as a centre helping families identify their lost ones. Elsewhere, designers responded to calls from emergency services. Norma Kamali pressed her team into the service of creating sleeping bags and coats from any fabrics they had at their disposal while others look inwards, with Carolina Herrera organising a group show for 11 young labels who had missed their opportunity to show. The event would become a precursor the the Vogue/CFDA Fashion Fund that has supported houses including Proenza Schouler, Altuzarra, Rodarte and many more. In the years that followed, and throughout the resulting two-decade long war in Afghanistan, the long-term response from fashion houses has been mixed. Some have partnered with charities working in the country to support those affected by the war while also protecting Afghanistan’s strong artisanal heritage. Burberry, for example, works with Oxfam to help ensure its cashmere is sourced sustainable and responsibly while NGOs such as Turquoise Mountain maintains a number of partnerships which have helped it grow Afghanistan’s artisanal sales tenfold to $1 million in 2018. In the wake of the war in Ukraine, however, it has become clear that the industry’s response to crises happening further afield pales in comparison to the way it reacts to those closer to home. Fashion’s aid during the coronavirus pandemicLike all industries that rely heavily on footfall and luring customers to buy physical products, the lockdowns of the coronavirus pandemic had a huge negative impact on fashion brands. This didn’t, however, prevent them from pitching in to help combat Covid-19 in any way possible. Direct donations formed a large part of the response, with houses including Tiffany & Co., LVMH, Kering, Prada, Dolce & Gabbana, Moncler, Versace, Armani and Valentino, making pledges in the millions to charities such as the Red Cross, World Health Organisation and UN Foundation, as well as to help local hospitals and research projects in their home countries. Smaller brands, such as Victoria Beckham and Everlane, promised a portion of their sales to charities such as Feeding America and the Trussell Trust, aiming to help those thrown into food insecurity by the pandemic. Elsewhere, houses put their supply chains to work creating vital equipment and PPE for frontline workers. LVMH and Kering both provided medical masks for the French health service, while the former also began producing sanitising gel. Lacoste’s factories, too, began producing reusable masks while Zara turned its factories into PPE centres for Spain’s first responders and Prada offered medical overalls, surgical masks and six intensive care units to hospitals in Milan. US brands also follow suit, with Christian Siriano and Brandon Maxwell creating and donating PPE to front line health care workers. In the UK many brands and retailers, including Sophia Webster, John Lewis, ASOS, Kurt Geiger, Missoma and Pronovias, offered discounts and donated items to NHS staff. Just as she had in response to 9/11, Norma Kamali once again began producing sleeping bag coats, selling them at half price when she realised how valuable they were for supporting a hospitality industry restricted to outdoor dining in the depths of winter. Fashion’s response to the war in UkraineWhile initially criticised for its slow response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine – with many suspecting brands were hesitant to pull out of the lucrative Russian luxury goods market resulting in an open letter from industry professionals pleading with brands to take action – major fashion companies did eventually offer significant support for those affected by the war. Support largely came in three main forms: charitable donations, removal of their products from Russia and fundraising events and special collections. Among the largest donations was LVMH, which gave €5 million to the International Committee of the Red Cross, while Valentino, Gucci, Kering, Christian Louboutin, Prada Group, Armani, Only The Brave Foundation (owner of Diesel, Maison Margiela, Marni, Viktor & Rolf, Amiri and Jil Sander), Isabel Marant and the National Chamber for Italian Fashion all made donations to UNHCR – the UN Refugee Agency. Elsewhere Chanel made a €2 million donation spilt between CARE International and UNHCR, Capri Holdings (owner of Versace, Jimmy Choo and Michael Kors) donated to the United Nations World Food Programmes and Louis Vuitton pledged €1 million to UNICEF, with whom it has a long-standing relationship. Balenciaga, meanwhile, gave over its social media accounts to the World Food Programme, as well as making a donation to the charity. Smaller brands, too, offers support with Erdem, Burberry and JW Anderson giving to the British Red Cross, Nanushka donating to the Hungarian Charity service of the Order of Malta, Rotate to the Danish Red Cross and Loewe supporting Spanish-based charity Cruz Roja Espanola. Marine Serre made a direct donation to Doctors Without Borders, as well as giving a percentage of sale from an ongoing pop-up to the cause and sending clothes, blankets and supplies to war victims. Conglomerates, such as Chanel and LVMH, also set up schemes to match any donations made by their staff. Prior to luxury goods being included in sanctions on Russia, many brands also took the move to halt retail in the country (though many said they would continue to pay Russian employees while stores were closed). These included Net-A-Porter, Rejina Pyo, Ganni, Asos, Nanushka, H&M, Nike, Hermes and Chanel, which even went so far as to restrict sales to anyone they thought might then take their purchases into Russia. By the end of the first month of the war the response from the fashion industry was one of the largest and most comprehensive reactions to an international crisis since the Second World War. Of course, the fashion industry’s collective response to the war in Ukraine – notably a European conflict affecting a largely white population in a nation in which many high-end brands operate – calls into question the lack of action in the face of many other humanitarian crises. Where, for example, were the donations to those affected by Serbia,’s invasion of Bosnia in the 1990s, or to the well-publicised famine in Africa? It is also telling that while fashion brands pulled together to help the American victims of 9/11, there was little follow up when it came to helping those in Afghanistan, Pakistan and other Middle Eastern countries whose lives were upended by the subsequent War on Terror. While the fashion world has shown it can be compassionate and generous, it is clear there is much to be learned in the face of future disasters. |

Search by typing & pressing enter