|

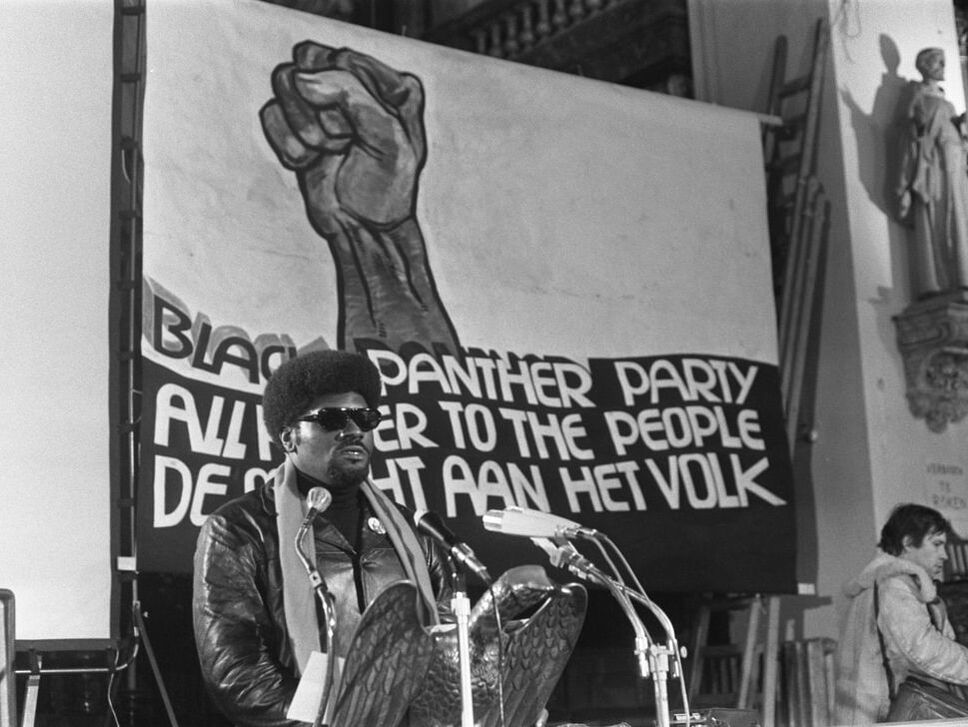

From the Suffragettes to Black Lives Matter, clothing has always been a way for the oppressed to speak out When Black Lives Matter protests broke out across the US, and internationally, in the wake of the George Floyd killing in May 2020, the images shared across social media and in the press were incredibly striking. Yes, because of the police brutality they depicted and because of the strength and courage of the protestors they portrayed. But also because of the face masks. Taking place, as the protests did, amid the raging coronavirus pandemic, almost every single protestor had covered half of his or her face with a mask. A necessary health precaution primarily but scrawled, as some were, with messages of defiance, they also became a uniform. A literal symbol of the silencing of black people by white privilege and systemic racism - made even more powerful by the clear evidence that coronavirus disproportionately affected BAME people. Seen in this way, the masks were made even more powerful by the very fact that protestors consciously dressed to be as anonymous as possible. While some sported Black Lives Matters T-shirts, a modern policing system which frequently uses images captured during demonstrations to identify and arrest protestors after the fact meant many sought to make themselves as unremarkable as possible. Advice shared by publications including Essence and Refinery29, as well as senator Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez, recommended wearing layers of block coloured, nondescript clothing and bringing a change of outfits. All highlighted the importance of comfort, protection and, ominously, the necessity of being able to run. What is striking about this advice is its stark contrast to the uniforms of past protests. Clothing has always been a key component of demonstrations but, traditionally, was used to mark oneself out from the crowd as a member of a certain group with certain beliefs - rather than an attempt to blend into the crowd for self-preservation. A clear example of this is the Suffragettes. So effective was the branding of the organisation that even today, a century after the protests, the mere sight of a purple, green and white colour combination immediately brings the cause to mind. In fact, the Suffragettes were so keenly aware of the impact their dress could have that Sylvia Pankhurst noted, “Many suffragists spend more money on clothes than they can comfortably afford, rather than run the risk of being considered outré, and doing harm to the cause.” Yes, the Suffragettes mays have resorted to arson and window smashing to make their point but they also understood that outright defiance of all feminine norms would get them nowhere. Rather, it was through a certain level of conformance and the ability to present themselves as appealing to the wider public that they would win the vote. It’s an interesting notion and one that Robin Givhan put under the microscope in the Washington Post when examining the clothing worn by activists in 1960s America. A tumultuous time characterised by ‘tribes’ each fighting to overcome their own separate oppressions, Givhan writes that, “The hippies shunned the materialism of the typical middle-class lifestyle. Black folks wanted equal access to it. And women wanted more control over it.” Clothes during this time were as much a sign of your politics as they were of your wealth and social standing. Hippies, usually white, wealthy and middle class, were granted the freedom to reject the fashionable trappings of this lifestyle while knowing that, when it comes to it, they were in danger of nothing more than a few disapproving looks as they went about their summer of love. For all their talk of peaceful protest, anti-war sentiments and free love, this was largely protest for protest’s sake. A youth culture designed to annoy while its participants knew they could return to the mainstream at any time. Women, too, were engaged in a wholesale rejection of expectations and ideals. Fighting for gender equality, their campaign was marked by an outspoken desire to rid themselves of the restrictions of bras, girdles, high heels and tight skirts. A largely white, well-off cohort, they picketed the Miss America pageant and provided ‘freedom trash cans’ in which women could physically rid themselves of objects they deemed oppressive. It is notable, then, that the group most discriminated against indulged in none of these style transgressions. Protesting, as they were, to be allowed into the comfortable, middle class spaces from which they had so long been unfairly barred, Civil Rights activists worked hard to outwardly embody the exact lifestyle they were striving to achieve. Their shirts were starched and their suits pressed. Theirs was a peaceful movement clad in polished dress shoes and conducted with proper posture. It was a look that said, “We’re no different from you” and, as Givhan notes, had huge visual impact. “When their racial diplomacy was met with a full, frontal attack, the images were especially jarring,” she writes. “What was so dangerous about these sport-jacketed men and pencil-skirt-wearing women that they should be repelled by the cannon blasts of fire hoses or the snarling bite of attack dogs?” The exception that proves the rule, of course, is the Black Panthers. Founded in the wake of the assassination of Malcolm X, the Black Panther Party was a radical response to the extreme racial inequity of 1960s America, with a Marxist philosophy based on targeted, practical measures rather than sweeping cultural ones. In contrast to the show of dignity their Sunday Best-wearing counterparts were displaying, the militant style of the Black Panthers played into stereotypical ideas of black people as aggressive, threatening and other. And while the party achieved many great things - from its free breakfasts for children programme to providing black communities with education, legal aid and healthcare - it was the organisation’s call to arm all African Americans that many remember it for. This, alongside its uniform of berets, leather, afros and beards, won the Black Panthers threat to national security status and more than a few high profile clashes with the police. However, while their conformists counterparts may have been more successful in achieving their aims in the short term, it is the image of the Black Panthers that has lived on as a symbol of black power in the long term. Referenced in modern pop culture by everyone from Beyonce to Kendrick Lamar, the iconic Black Panther look has achieved such sanctity and reverence that, as Marissa Lee notes in Mission Mag, it has been spared the cultural appropriation by white designers and influencers so commonly afflicted upon other non-white styles. And, while the democratisation of fashion has seen modern protests become a blur of jeans and hoodies, each participant willed through threat of violence and arrest to look as much like their neighbour as possible, clothing will continue to be a major part of protest movements. Be it a slogan T-shirt, a meaningful colour combination or an all-out uniform, when your voice is taken your clothing can do the talking for you. Comments are closed.

|

Categories |

Search by typing & pressing enter